All Understanding is Visual: Why Aristotle Writes With Pictures

Imagery in writing is not an accident, but an insight into how our minds work.

Sometimes when I’m reading bedtime stories to my five-year-old, I glance at her and wonder Is she following this? We recently made the jump to “chapter books,” starting with some that have illustrations on every page. She often stops me and says “Let me see.” She’ll grab the book and pull it up to her nose to study the pictures.

Pictures seem to be at the core of how we understand anything. People often say “I’m a visual learner” as if it were a matter of personal style. (Where are all the audio learners? Taste learners?) I’m no neuroscientist, but it seems to me that everyone is a visual learner.

The fact that great writing is rich in imagery is not some accidental aesthetic quirk (like the fact that pavement always appears wet in movies), but an insight into how our minds work. I first encountered this idea reading Steven Pinker, but Aristotle gave me a renewed appreciation for it.

In The Stuff of Thought, Pinker highlights that language is inherently better at encoding certain types of data (emphasis mine):

Language gives us the means to share an unlimited number of combinations of ideas about who did what to whom, and about what is where... (but) language is notoriously poor at conveying the subtlety and richness of sensations like smells and sounds. (276)

Aristotle makes a stronger claim—that it’s not just sight and language that are closely connected, but sight and knowledge. This special connection is so fundamental to Aristotle that he devotes the first words of the Metaphysics to it:

All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight... The reason is that this, most of all senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things. (980a22)

The insights of Pinker and Aristotle point in a very practical direction: If we wish to be understood, we should speak in pictures. This is especially true when discussing abstract topics, as Aristotle does in Metaphysics and De Anima. As we’ll see, his use of mental imagery is made even more powerful by developing them into metaphors.

Understanding the Soul: A Case Study in Mental Images and Metaphors

De Anima is Aristotle’s investigation of the soul. As he reasons through the nature of the soul, whether it has parts, and whether there are different types of soul, he uses imagery and metaphors to make his ideas more concrete and understandable.

Aristotle defines the soul using a concept he calls actualization, (emphasis mine):

For something is said to be a substance, as we mentioned, in three ways, as form, as matter, and as what is composed of both. And of these, the matter is potentiality, the form is actuality. And since what is composed of the two is an animate thing, the body is not the actualization of the soul, but rather the soul is the actualization of a certain sort of body. (414a13)

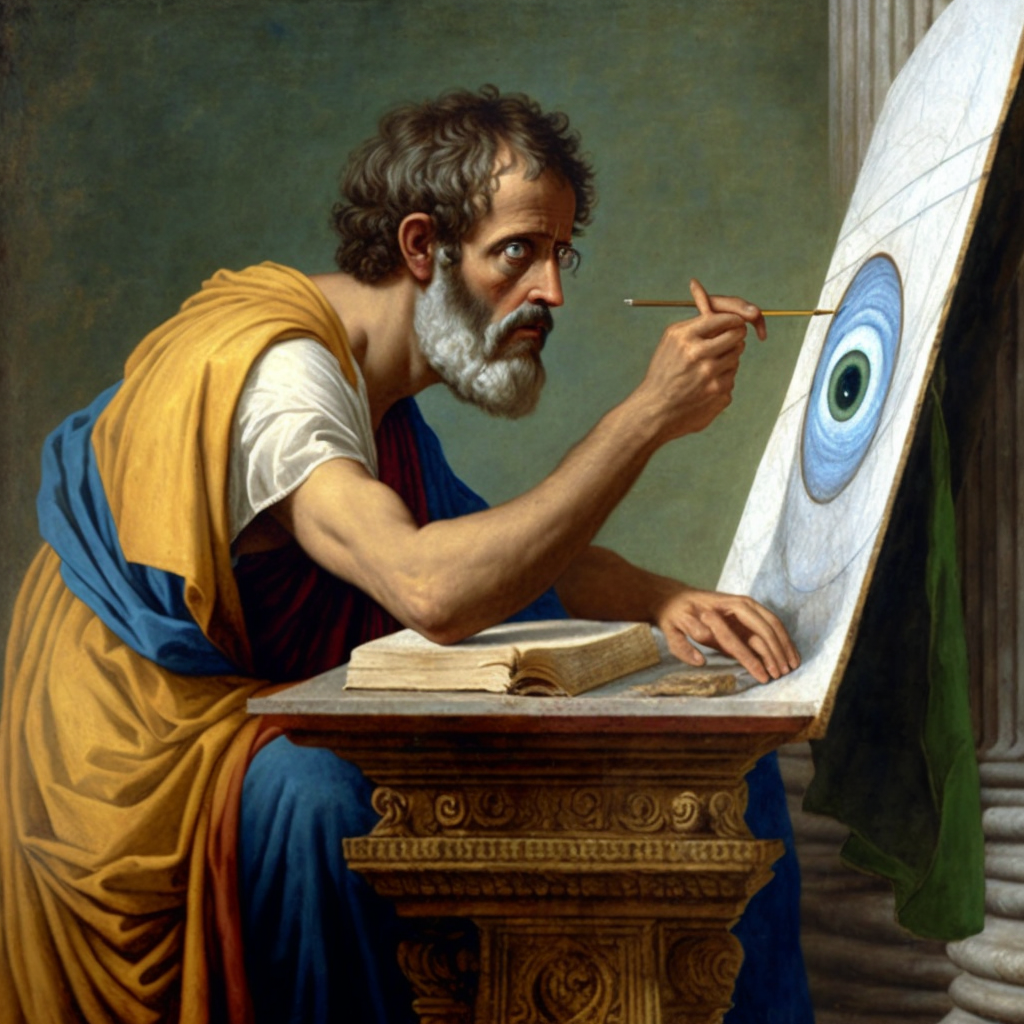

The ideas of actualization and potentiality may seem flat and hard to grasp at first, but Aristotle brings them to life with mental images and metaphors. One of the more striking mental images he employs is (appropriately for this essay) an eye.

An eye, he explains, is actualized when it is able to see. “If this fails, it is no longer an eye,” he writes, “like an eye in stone or in a picture.”

The “eye in stone” prevents us, as readers, from being lost in layers of abstraction. We now have a mental image that tethers our thoughts to Aristotle’s argument, like an illustration in a child’s bedtime story. On top of this image, Aristotle constructs layers of metaphor:

- First layer: A stone eye is like a blind eye because neither has sight (the defining trait that makes an eye an eye)

- Second layer: Sight for an eye is like soul for a body because each is the fulfillment of a certain kind of purpose or potential.

Actualization, therefore, is the fulfillment of a certain potential or purpose. A body’s potential is to be alive, so the soul is the defining characteristic of a living body.

Aristotle’s conception of the soul runs counter to Plato’s Phaedo, in which Socrates argues that death liberates the soul from the body. To Socrates, death is the actualization of the philosopher’s pursuit of knowledge:

It really has been shown to us that, if we are ever to have pure knowledge, we must escape from the body and observe things in themselves with the soul by itself... for if it is impossible to attain any pure knowledge with the body, then one of two things is true: either we can never attain knowledge or we can do so after death. (66e)

Of course to Aristotle, Socrates’s notion that a soul could exist without the body is like vision existing without eyes: It doesn’t make sense.

The Architecture of Ideas

Most of us aren’t writing philosophical treatises or novels. When we talk about “storytelling,” we’re often referring to business communication. But even PowerPoint presentations share one important trait with philosophy: They are often abstract and difficult to follow.

Without characters and plot lines, business communicators and philosophers face a common challenge: How can we keep our audience interested? One answer is to do what Aristotle did in De Anima: Become an architect of ideas and show, don’t tell. Use mental images as bricks and metaphors to structure those bricks into something meaningful.

Unlike the books I read my daughter at night, your stories probably aren’t meant to put people to sleep. You want to be listened to and remembered. So take a page from Aristotle. Think less about words, and more about pictures.